Reviving Wards in Charlottesville

"We want to choose our own man."

This is the third piece in a series tracing the historic roots of Charlottesville's former block voting system. You can learn more about how block voting works and why it spread in the first two installments.

For more than 50 years, Charlottesville's block voting system worked as intended, concentrating power among white and affluent voters while excluding minority voices from city government. Without representation on City Council, minority voters had few paths to reform.

That changed in 1965, when the federal Voting Rights Act gave minority communities new legal tools to challenge winner-take-all elections. The Act provided minority voters with a right to elect candidates of their choice, not just candidates chosen by the majority group or party leaders. Even if a white-majority city happened to elect some Black candidates using block voting, Black voters were still entitled to a voting system that allowed them to select winners on their own — in proportion to their share of the electorate. In the 1970s, the Department of Justice used the Act to force Richmond and Petersburg to abandon block voting and adopt ward systems, establishing precedent for reviving ward elections in Virginia.

Rather than pursue federal litigation, Charlottesville's local branch of the NAACP chose to lobby City Council directly for reform. The branch launched its campaign in the spring of 1979, when all five members of Charlottesville's City Council were white. The city's first-ever Black councilor, Charles Barbour, had chosen not to run for a third term in 1978, and the only Black candidate that cycle, James Hicks, lost by 175 votes, leaving Charlottesville with an all-white council after eight years of breakthrough leadership.

In April 1979, the NAACP presented City Council with a petition signed by 500 voters calling on Council to reinstate ward elections. The branch's Political Action Committee chair, Virginia Carrington, asserted Black voters' right to elect a candidate of their choice in her testimony to Council. "Usually the Democrats will choose someone," she said. "But we don't want this anymore. We want to choose our own man."

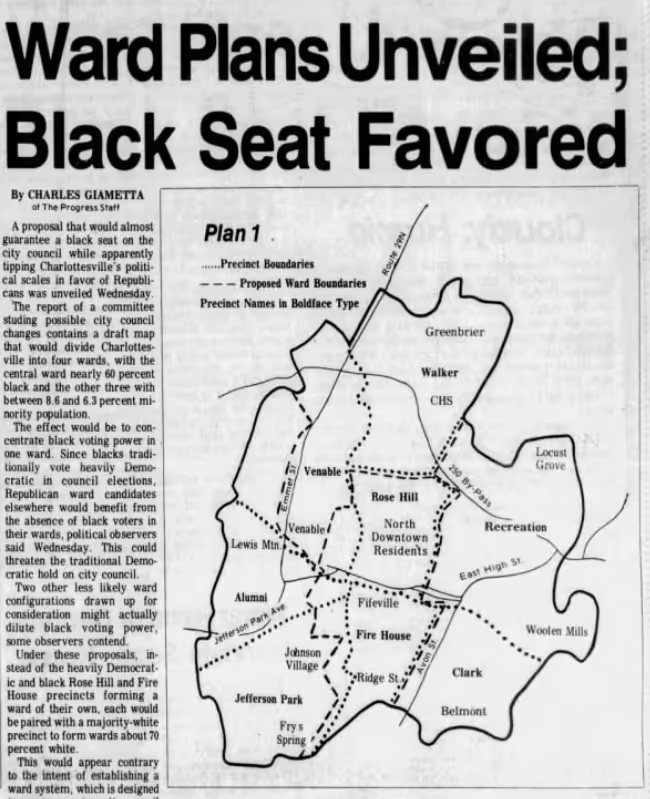

In the year that followed, the NAACP lobbied City Council to form a citizen commission to study expanding the Council to seven members and adopting wards, at-large seats, or a mix of both. After the 1980 election brought three reform candidates to Council, the new majority agreed to the study. The commission delivered its proposal in September 1981, endorsing a mixed-ward system with four ward members and three at-large seats. The ward map created a central ward with nearly 60% Black voters by combining the Rose Hill, Fifeville, and Ridge Street neighborhoods while concentrating white voters in the other three wards.

The commission acknowledged both the potential and limitations of a ward voting system. As the Daily Progress noted, the central ward design "would almost guarantee a black seat" and provide long-overdue representation for neighborhoods like Fifeville and Belmont that hadn't seen a resident serve on City Council in more than 20 years. But wards also raised concerns among Black residents. Urban renewal was already displacing some of Charlottesville's historically-Black neighborhoods, casting doubt on whether the central ward would reliably elect a Black candidate for long. The ward system could also create challenges for Black candidates themselves. A Black politician who didn't happen to live in the majority-Black ward could find it harder to get elected in a district drawn for white voters. Democratic Party leaders also feared that packing Black voters in one ward would make Republicans more competitive in the other districts, threatening Democrats' majority on Council.

Rather than vote directly on the ward plan themselves, City Council asked for resident input through a referendum in November 1981. The ward proposal passed that fall by a narrow margin of 52% to 48%. But Council rejected the outcome, citing the close results and brief window for public debate between the proposal’s release and November election. The Council called for a second vote in May of 1982, when only local matters would be on the ballot. Ward opponents organized a serious opposition campaign — over objections from some NAACP leaders that Council had rejected the will of the voters — and when residents voted again that May, the ward proposal failed 58% to 42% among less than 6,000 voters.

Though the council members had legal authority to adopt the ward plan with or without voter support, they chose to heed the second referendum and maintain the block voting system that got them elected. After the failed 1982 campaign, state NAACP leaders focused their election reform work on other Virginia cities, leaving Charlottesville's block voting system intact.

The failed referendum would haunt election reform efforts in Charlottesville for decades. Learn more about how the 1982 defeat undermined reform debates in the early 2000s in the fourth installment of this five-part series.